Young people

Younger adults aged 16 to 29 years are more likely than those in older age groups to report feeling lonely ‘often or always’ [1].

- Research from the Co-Op Foundation found that only 5% of young people say they never feel lonely [2].

- University students are likely to experience loneliness: nearly 1 in 4 students feel lonely ‘all’ or ‘most’ of the time [3].

- International students are considered to be at particularly high risk of loneliness, and may experience ‘cultural loneliness’ [4].

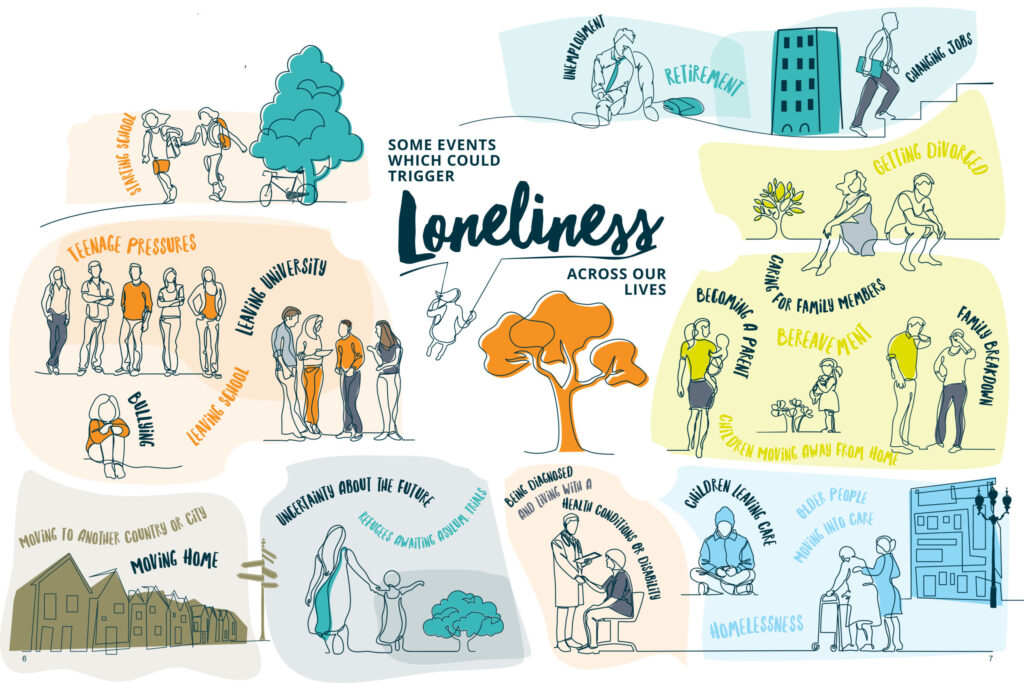

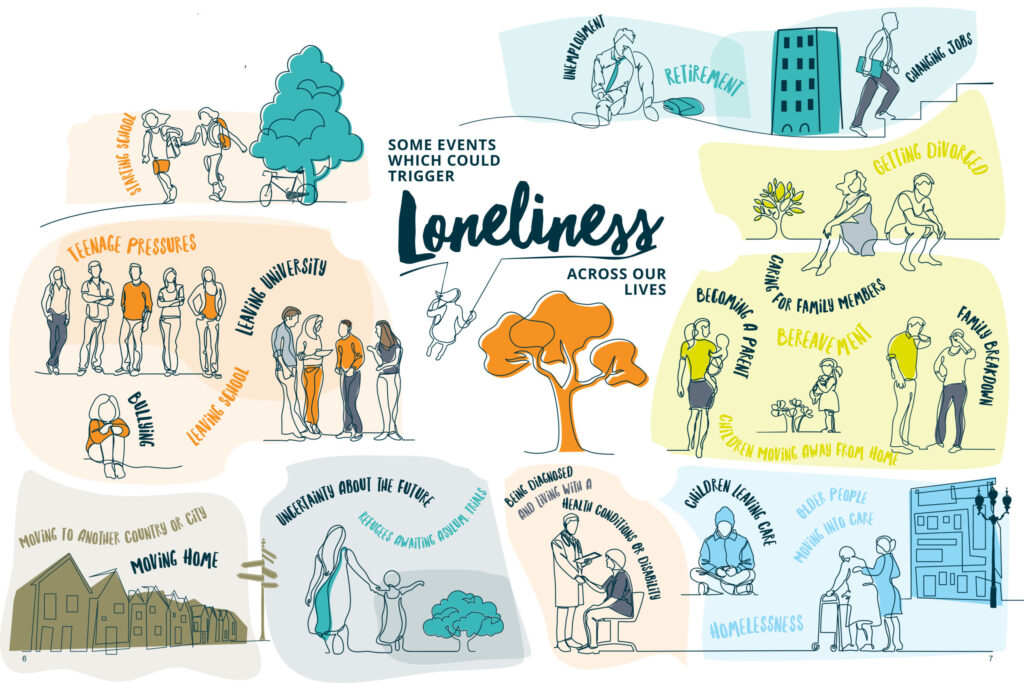

Different reasons have been suggested for why young people might feel so lonely. Experiences of bullying, moving schools, illness or disability, changes in family circumstances or not getting on with family, and isolation from the pandemic could all contribute to loneliness.

- Milestones like leaving or furthering education, seeking employment, moving out of the parental home, and establishing long-term romantic relationships could all alter social networks [5].

- 16-24 year olds might have less experience of regulating intense emotions, or of loneliness in general, due to their age [6].

- 55% of lonely young people said that ‘not having money to attend or take part in activities’ impacts how lonely they feel [2]. This is especially pertinent during the cost of living crisis [7].

- Social media may also be a contributing factor: 56% of young people say ‘seeing friends having fun on social media has a negative impact’ [2].

Much of the research and evidence on loneliness focuses on people aged over 16. However, in recent years there has been an increasing focus on loneliness in children:

- Loneliness is more prevalent in children (aged 11-15) from lower socio-economic backgrounds [8]

- Negative peer relationships (such as being the victim of bullying) can increase a child’s risk of loneliness [9]

Older people

As we get older, risk factors that might lead to loneliness can begin to increase and converge – once we have one risk factor, we may start having more. This can make the experience of loneliness hard to change, particularly in older age. Key risk factors associated with older age include (but are not limited to) [10]:

- Facing bereavement

- Living alone

- Living with limiting disabilities or illnesses

- Caring for a partner

- Physical and mental health difficulties, making it harder to participate in activities and maintain relationships

- Low fixed incomes, such as pensions, making activities unaffordable

- Digital exclusion

- Reduced mobility and loss of access to affordable, reliable, and/or suitable modes of transport

Specific life circumstances can make older people vulnerable to loneliness, like retirement, being widowed, and being socially isolated. According to AgeUK, people aged 50 and over living in England are [11]:

- 5.5 times more likely to be lonely if they don’t have someone to open up to when they need to

- 5.2 times more likely to be often lonely if they are widowed

- 3.7 times more likely to be often lonely if they are in poor health

Before the covid-19 pandemic, about 1 in 12 people aged 50+ in England were often lonely. This is equivalent to around 1.4 million people, and AgeUK estimate that this will increase to around 2 million by 2026 [10].

Gender identity and sexual orientation

Evidence doesn’t seem to suggest that one gender is more lonely than the other. Research from 2019 showed that levels of loneliness across the lifespan tend to be broadly similar for men and women [12].

So in general, there is no great difference – although the most recent survey data suggests that in Britain in the last few years, women have been lonelier. Loneliness seemed to disproportionately affect women during the pandemic [13]. Research from the NHS has shown that [14]:

- Women (24%) are slightly more likely than men (20%) to feel lonely at least some of the time

- Men (32%) are more likely than women (22%) to report never feeling lonely

For chronic loneliness specifically, the levels have been similar for men and women in recent years. Recent statistics from the ONS show that 7.7% of women, and 6.3% of men, experience chronic loneliness. This slight difference may be explained by the overall increase in women’s loneliness in these figures.

Loneliness can affect people of different genders in different ways, so responses to loneliness can vary based on need. For example, Men in Sheds targets mens’ connection, while other groups focus on bringing women together, like London Lonely Girls Club. It is also possible that exposure to risk factors can vary by gender [15].

LGBTQ+ people are at a greater risk of loneliness [16]. Recent evidence in this area is limited, but so far shows that:

- Social rejection, exclusion, and discrimination can lead LGBTQ people to feel more lonely [17].

- Older lesbian and gay people seem to be lonelier than their heterosexual counterparts [18].

- Older LGBT people are particularly vulnerable to loneliness, as they are more likely to be single, living alone, and have less contact with relatives [19].

A 2023 study found high rates of loneliness and social isolation among transgender and gender diverse people [20]. A report on trans mental health found that, on a scale of 1 (never feeling isolated) to 7 (constant isolation), the average score was 3.9 – indicating a significant level of isolation among trans people [21].

Internalised stigma seems to correlate with loneliness amongst lesbian, gay, and bisexual people [22]. Belonging to a sexual minority can be a risk factor for loneliness, with minority stress a contributing factor [23], as well as experiences of sexual orientation discrimination [24].

Ethnic minorities

There is a mixed picture on whether people from ethnic minorities are more likely to be lonely, while there is clear evidence of the impact of discrimination on loneliness:

- During the pandemic, people from ethnic minority backgrounds (23%) were more likely to experience loneliness compared to people from white backgrounds (17%) [13].

- Older Black and Asian adults are more likely to report having fewer close friends and friends who live locally [25].

- In the workplace, workers from ethnic minorities are more likely to feel that they often or always have no one to talk to at work (13%), compared to white workers (9%) [26].

- People from BAME backgrounds more frequently report feeling they are less able to access community activities and support [27].

Much of the data on loneliness comes from a white British context. To address this gap, the British Red Cross conducted research on loneliness in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic community (BAME) communities. They found that:

- 38% of people whose ethnicity is Black, Asian, or minority ethnic say that they often feel alone, like they have no one to turn to – compared to 28% of people of white ethnicity [28]

- Racism, discrimination, and xenophobia seem to be related to loneliness. ‘Almost half of people (49%) who had experienced discrimination at work or in their local neighbourhood reported being always or often lonely, compared with just over a quarter (28%) of people who hadn’t’ [27]

Health and disability

People who have poor mental health, a long-term health condition, or a disability are at an increased risk of loneliness.

- 62% of adults in England who reported bad or very bad health say they feel lonely some of the time, compared to 35% of adults with fair health, and 18% with good or very good health [14].

- According to Sense, 61% of disabled people are chronically lonely, meaning they feel lonely ‘often’ or ‘always’. This rises to 70% for young disabled people aged 16 to 24 [29].

- In the workplace, disabled workers and those with long-term health conditions that affect their day-to-today lives are much more likely to report loneliness (24%) than those without (9%) [26].

- Over a third (36%) of people with learning disabilities feel lonely nearly always, or all the time [30].

Families, parents and carers

Family circumstances can contribute to loneliness, such as: adult children leaving home, bereavement, becoming single, weak familial relationships, and being at home with young children [31]. Becoming a parent can also contribute, especially at a young age:

- 83% of mothers under 30 feel lonely at least some of the time [32]

- 43% of mothers under 30 feel lonely often or always [32]

- Pregnant people and new parents who experience additional hardships (e.g. immigrants, non-binary people, parents with postpartum depression) [33], lack social support [34] or feel isolated [35] may be at a higher risk of loneliness.

People who are carers can feel particularly lonely, especially if they need to change their lifestyle or can no longer take part in hobbies and activities.

- Carers are seven times more likely to say they often or always feel lonely, compared to the general population [36]

- 81% of carers have felt lonely or socially isolated as a result of their caring role [36]

Looking after a child with additional needs also appears to be a risk factor for loneliness. One study found that loneliness was higher among parents of autistic children [37].

Socio-economic status and local area

Loneliness has been found to be higher in people who are from lower socio-economic backgrounds [38], or who live in a socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhood [39].

- Recent NHS research found that the amount of adults feeling lonely at least some of the time was higher in lower income households: 27% and 28% in the lowest income groups, compared to 18% and 20% for higher income groups [14]

- In London, we co-authored a study that found people with a high debt burden or living with food insecurity were both more than twice as likely to be chronically lonely than people who had no debts or no food insecurity [40]

- A study in England found an association between loneliness and social inequality in secondary school-age children and adolescents [41]

This unequal distribution of loneliness could be due to inequity in resources like employment, education, access to health services and public transport [39]. Limited finances means that people might not be able to afford activities or opportunities to socialise.

Geographical areas and surroundings can also influence someone’s chances of being lonely. Read more in our 2022 report on Tackling loneliness through the built environment.

- Adults in the most deprived areas were more likely to report feeling lonely at least some of the time (32%), and were more likely to report chronic loneliness (10%) [14].

- Living in different areas can alter the impact of sociodemographic risk factors for loneliness. So, for example, being in a sexual minority can make more or less of a difference depending on where you are [42].

- The local built environment can also contribute to loneliness. Some places are more conducive to social connection – for example, green spaces which are safe and accessible, bumping spaces where we might see ‘weak ties’ like acquaintances, or places and activities where we can build ‘strong ties’ through real friendship [43].

The cost of living crisis only exacerbates this issue, limiting opportunities for social connection, and contributing to poorer mental health (which can in turn be a risk factor for loneliness).

- ONS data from 2022 showed that adults who reported feeling worried about the rising costs of living reported worse scores on wellbeing, including higher levels of loneliness [44]. These findings do not discuss causality, but do seem to indicate some association between cost of living anxieties and feelings of loneliness.

Personal circumstances

Personal circumstances – like living situation, or significant life changes – can increase someone’s likelihood of experiencing loneliness.

Risk factors (in addition to those listed above) include:

- not living with a partner [45]

- having recently moved house [45]

- being out of work [45]

- ‘trigger events’ like migration, becoming a carer, bereavement, a new baby, moving home or job, or children leaving home [46].

What Works Centre for Wellbeing